Addressing Ambiguity

A Clarity Framework for uncovering assumptions, resolving unknowns and eliminating hidden work before it derails your project.

Purpose

Every project begins with an agreement. Stakeholders align on goals, timelines, deliverables and success criteria. Everyone leaves the room confident they are on the same page.

They are not.

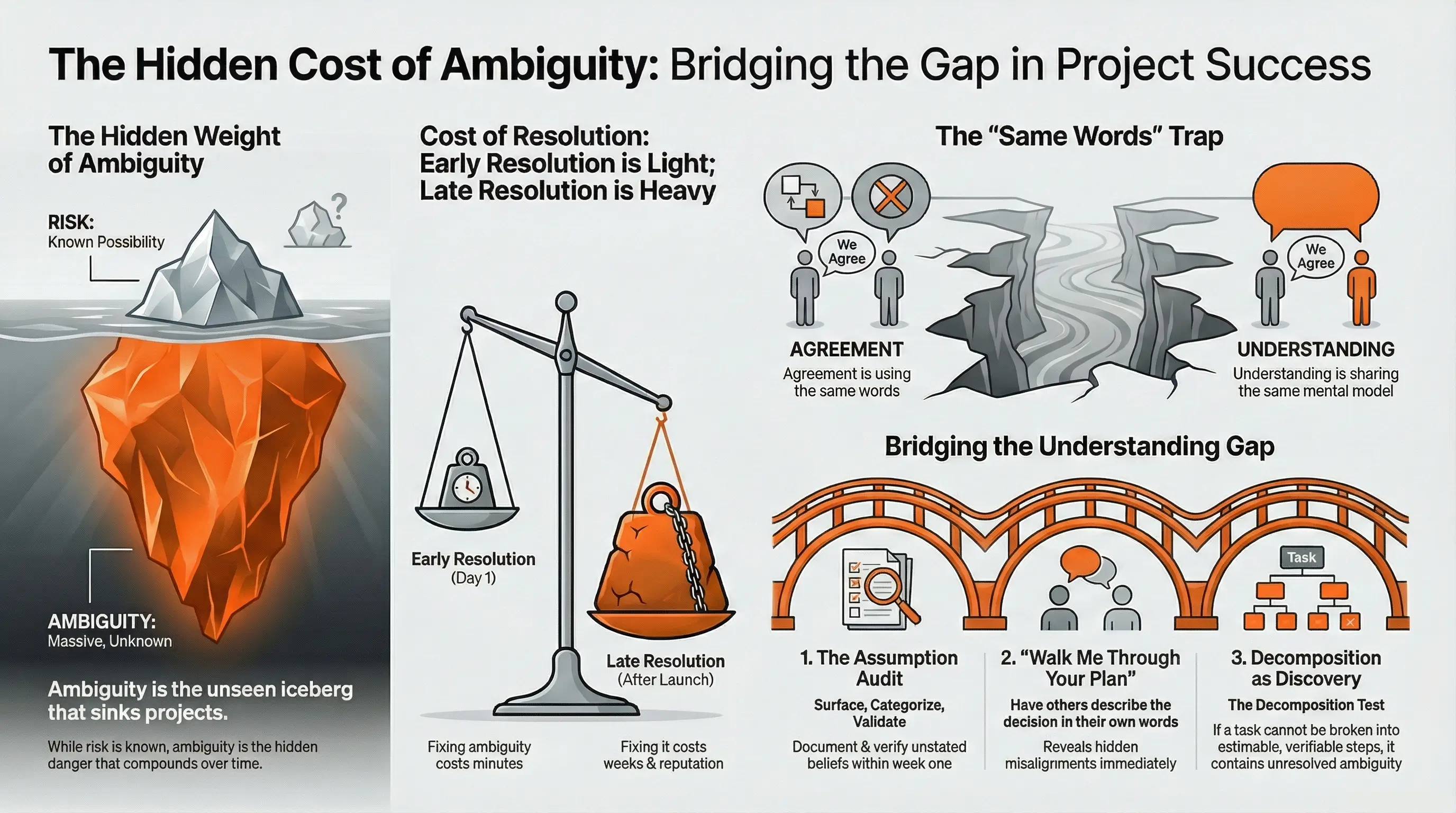

The words were the same, the mental models behind them were different. One person heard "minimal viable product" and pictured a lean prototype to validate assumptions. Another heard the same phrase and pictured a polished, production-ready system. Both believed they agreed. Neither checked.

This is ambiguity, the gap between what people believe they agreed on and what they actually understood. It is not a failure of communication, it is a structural feature of complex work. The more people involved, the more disciplines represented, the more assumptions embedded in a plan, the wider the gap becomes.

Ambiguity is not the same as risk. Risk is something you know might go wrong. Ambiguity is something you do not yet know you need to clarify. It hides in the spaces between words, in the deliverables everyone assumes are straightforward, in the questions no one thought to ask because the answer seemed obvious.

Left unaddressed, ambiguity does not resolve itself. It compounds. Small misunderstandings become entrenched assumptions. Entrenched assumptions become conflicting expectations. Conflicting expectations become rework, frustration and broken trust, usually surfacing at the worst possible moment, when the cost of correction is highest. Every project pays for ambiguity. The only question is when.

Ambiguity resolved early is cheap. A conversation, a whiteboard session, a document that captures what "done" actually means. It costs minutes or hours. Ambiguity resolved late is expensive: a deliverable reworked because the team built what they understood, not what the stakeholder intended; a dependency that slips because two teams had different assumptions about what was being handed off; a launch delayed because "production-ready" meant different things to engineering and operations. Ambiguity that is never resolved is the most expensive of all, a permanent source of friction, recurring disagreements, repeated rework, eroding trust.

This is why the beginning of a project, the phase most often rushed through in excitement to start building, is precisely when the investment in addressing ambiguity pays the highest return. Changing a requirement on day one costs nothing. Changing it after six weeks of development costs rework, schedule impact and stakeholder confidence. Changing it after launch costs all of that plus customer impact and reputation. Every hour spent clarifying assumptions in the first two weeks saves days or weeks of correction later.

Addressing Ambiguity is the discipline of hunting for these gaps early, making the implicit explicit and converting unknowns into shared understanding while there is still time to act on what you learn. The teams that consistently deliver are not the ones with the fewest ambiguities. They are the ones who find and resolve them earliest.

The Assumption Audit

Ambiguity hides in the parts of the plan that feel settled, in agreements where people used the same words but understood them differently, in scope boundaries where two teams each believe the other is responsible, in dependencies where definitions of "what we are delivering" quietly diverge, in success criteria no one pinned down and in process decisions no one made explicitly. It feeds on assumptions, things people believe to be true that have never been stated, examined or validated.

Every project is built on a foundation of assumptions. Most are reasonable. Some are wrong. The Assumption Audit is a structured practice for finding out which is which before it matters.

How to run an Assumption Audit:

Gather the core team early in the project, ideally within the first week. The goal is to surface, document and validate the assumptions embedded in the plan.

Step 1: Surface. Ask each team member, individually or as a group, to list their assumptions across key categories. Do not filter. Do not debate. Just capture.

Step 2: Categorise. Group assumptions by domain:

- Features and scope: What exactly are we building? What platforms, browsers, devices? What is explicitly excluded? What does "minimum viable" mean for this project?

- Dates and milestones: Is the completion date when code is complete, when testing starts or when the product is released? Are interim milestones fixed or aspirational?

- Team and resources: Are team members fully dedicated or shared? What skills do we have? What skills are we assuming we can acquire?

- Priorities and trade-offs: Is the top priority the deadline, the full scope or the budget? What ranks second? (This connects directly to the Tradeoff Triangle, run that conversation alongside the Assumption Audit.)

- Quality and standards: Are we optimising for speed or quality? What does "tested" mean? Who is responsible for quality assurance?

- Dependencies: What are we expecting from other teams? What format, timeline and quality? Have they confirmed?

- Process and communication: How will we share status? Who needs to approve what? How frequent are updates? What tools will we use?

Step 3: Validate. For each assumption, ask: has this been confirmed? By whom? If the answer is "no" or "I think so," it needs validation. Assign an owner and a deadline for each unvalidated assumption.

Step 4: Document. Write the validated assumptions down in a shared location. This becomes a living reference, a record of what the team agreed on that can be revisited when disagreements arise.

Step 5: Back-brief. After any significant agreement, ask the other party to describe in their own words what was just decided. Not "do you understand?" (everyone says yes) but "can you walk me through what you are going to do?" The gap between what was said and what was heard becomes immediately visible. This single practice catches more misalignment than any amount of documentation.

A real example:

A project manager once had a serious disagreement with a client over the definition of "minimal viable product." The client believed this meant a product that was mature, sophisticated, well-tested and well-polished, essentially a finished product with fewer features. The project manager understood it as a lean prototype to test assumptions. Both had been operating on their interpretation for weeks. The cost of resolving this assumption on day one would have been a five-minute conversation. The cost of resolving it after weeks of development was a project reset.

The Assumption Audit exists to catch these moments before they become expensive.

Decomposition as Discovery

Large tasks are ambiguity's favourite hiding place. A deliverable estimated at two weeks sounds manageable. But can you describe, in concrete steps, what happens in those two weeks? If the answer is vague, "we will build the integration," then you do not have a plan. You have a hope.

There is a prevailing belief, particularly in agile environments, that detailed upfront thinking is wasteful, that the team should start building and let the work reveal itself. This sounds efficient. In practice, it often means spending five days coding to avoid spending one day thinking. The ambiguity does not disappear because you started work. It simply surfaces later, as rework, as conflict, as the slow realisation that the team has been building toward different interpretations of the same requirement.

Decomposition, breaking large deliverables into smaller, clearly defined steps, is not just a planning technique. It is a discovery tool. The act of breaking work down forces you to confront what you actually know and what you are assuming. This is not waterfall. It is not asking you to predict the future in detail. It is asking you to think clearly about what you are about to do, so that when you start building, you are building the right thing.

What decomposition reveals:

-

Hidden complexity. A task that seemed straightforward contains sub-tasks that are individually complex. "Build the API" turns out to mean authentication, rate limiting, error handling, documentation, versioning and monitoring. Each of these has its own ambiguities.

-

Missing knowledge. The team cannot describe the steps because they do not yet understand the work well enough. This is not a failure, it is valuable information. It tells you where investigation is needed before execution can begin.

-

Dependencies. Breaking work into steps reveals sequential dependencies that were invisible at the higher level. Step three requires output from another team that has not been requested. Step five requires a decision that has not been made.

-

Estimation gaps. A two-week estimate for a monolithic task is a guess. Estimates for smaller, well-defined steps are more reliable. The sum of the parts often reveals that the original estimate was optimistic, or occasionally that it was conservative. Either way, you have better information.

The decomposition test:

If a task cannot be broken into steps that are each estimable, assignable and verifiable, it contains unresolved ambiguity. The inability to decompose is itself a signal, and often the most important one. Do not push forward with a task you cannot describe. Invest the time to understand it first.

Front-Loading Uncertainty

Teams gravitate toward the work they understand, the tasks that are clear, well-defined and satisfying to complete. The ambiguous work gets deferred. "We will figure that out when we get to it." This means the hardest problems are tackled when the project has the least time and flexibility to absorb what they reveal.

Schedule the work you understand least for the earliest possible moment. This is not about doing the hardest work first for its own sake. It is about converting ambiguity into knowledge while you still have room to adapt. Starting early means questions surface early, estimates become more reliable and if the plan needs to change, you have time to adjust. Late discovery leaves no room for adjustment, only crisis management.

Sometimes front-loading means building, not just planning. When ambiguity cannot be resolved through conversation alone, a time-boxed spike, a small proof-of-concept built to answer a specific question, is one of the most effective tools available. Build just enough to learn what you need to know, then decide how to proceed.

This principle connects directly to Risk Management. Unresolved ambiguity is, in effect, a risk you have not yet identified. Front-loading uncertain work is both an ambiguity resolution strategy and a risk mitigation strategy. The Aspirational Review applies a related technique to individual performance: imagining a successful outcome in detail and working backwards to identify what must be true for it to happen. The same mental move, inverted to imagine failure, is equally powerful for surfacing project-level assumptions the team has not examined.

Building an Ambiguity-Friendly Team

None of the practices above work if the team does not feel safe raising ambiguity in the first place. Ambiguity often stays hidden, not because no one sees it, but because no one wants to be the person who slows things down by asking what seems like an obvious question.

If you lead a team, creating the conditions for ambiguity to be surfaced is one of the highest-leverage things you can do. This is not about running more meetings or adding more process. It is about behaviour.

Celebrate early ambiguity. When someone raises a question that reveals an assumption the team had not examined, recognise it explicitly. "That is a great catch, we would have discovered this the hard way in three weeks." Make it clear that finding ambiguity early is a contribution, not a disruption.

Model it yourself. Leaders who pretend to have all the answers teach their teams to do the same. Leaders who say "I am not sure we have this figured out, let us dig in" give everyone permission to do likewise.

Make it safe to say "I do not understand." In many teams, admitting confusion is seen as incompetence. In healthy teams, it is seen as rigour. The person who says "I do not understand how this is supposed to work" is doing the team a service. Make sure they know it.

Normalise the practice. Build assumption audits and decomposition exercises into the project cadence, not as extra overhead but as standard practice. When these activities are routine, raising ambiguity stops feeling like raising an alarm and starts feeling like doing the job.

This connects to the Transparency Principle. A culture where people share what they know, including what they do not know, is a culture where ambiguity gets resolved early. A culture where information is hoarded and uncertainty is hidden is a culture where ambiguity compounds until it detonates.

Signs Addressing Ambiguity Is Working

- Assumptions are documented and validated in the first week of a project

- Stakeholders converge on shared definitions before significant work begins

- The team can decompose every major deliverable into concrete, estimable steps

- Ambiguity is surfaced by team members at all levels without hesitation

- Surprises decrease as the project progresses, the team learns the important things early

- Rework due to misaligned expectations is rare

- The most uncertain work is scheduled early, not deferred

- Disagreements are about genuine trade-offs, not about what was originally agreed

Signs Addressing Ambiguity Is Broken

- "We agreed on this" is a frequent source of conflict

- The same deliverable gets reworked multiple times because expectations differed

- Large tasks sit in the plan as monolithic blocks that no one can describe in detail

- Ambiguity is treated as someone else's problem, "that is for the BA to figure out"

- Team members avoid raising questions for fear of looking uninformed or slowing things down

- The hardest, murkiest work is deferred to the end of the project

- Assumptions are discovered only when they prove wrong

- Dependencies surprise the team because no one clarified what was actually being delivered

- Post-mortems repeatedly identify "miscommunication" as a root cause

Summary

Addressing Ambiguity is the discipline of uncovering assumptions, resolving unknowns and eliminating hidden work before it derails your project.

Every project is built on a foundation of assumptions, about scope, priorities, definitions, dependencies and process. Most are reasonable. Some are wrong. The difference between projects that deliver and projects that stumble is not whether ambiguity exists, it always does, but whether the team finds it early enough to do something about it.

The practices are straightforward: audit assumptions systematically, decompose large tasks to reveal hidden complexity, front-load uncertain work to convert unknowns into knowledge and build a team culture where surfacing ambiguity is celebrated rather than penalised.

Ambiguity resolved early costs minutes. Ambiguity resolved late costs weeks. Ambiguity never resolved costs trust. The best time to address it is before you start building. The second best time is right now.

Are assumptions hiding in your project plans?

Clarity Forge surfaces ambiguity early, so your team builds toward the same outcome, not different interpretations of one.

Book a DemoStart Free TrialA discussion to see if Clarity Forge is right for your organization.

Stay in the loop

New frameworks, articles and guides — straight to your inbox.

About the Author

Michael O'Connor

Michael O'ConnorFounder of Clarity Forge. 30+ years in technology leadership at Microsoft, GoTo and multiple startups. Passionate about building tools that bring clarity to how organisations align, execute, grow and engage.